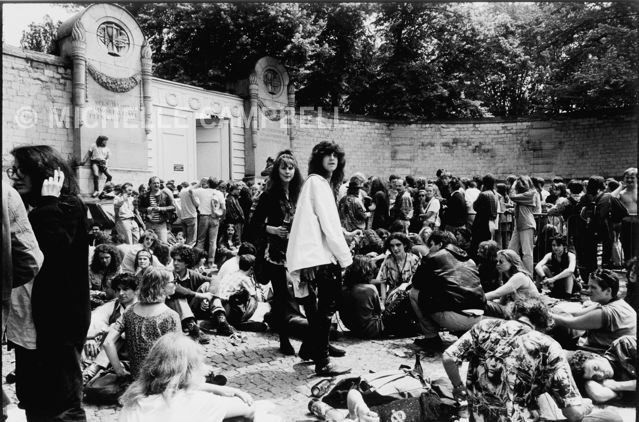

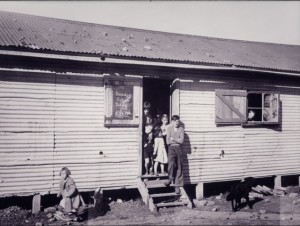

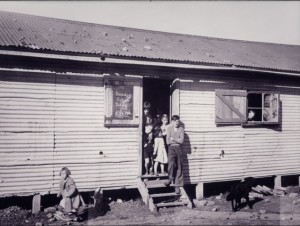

Kids waiting for Sunday School to open at Camp Pell late 1940s. They carried the moral stain of growing up there for years.

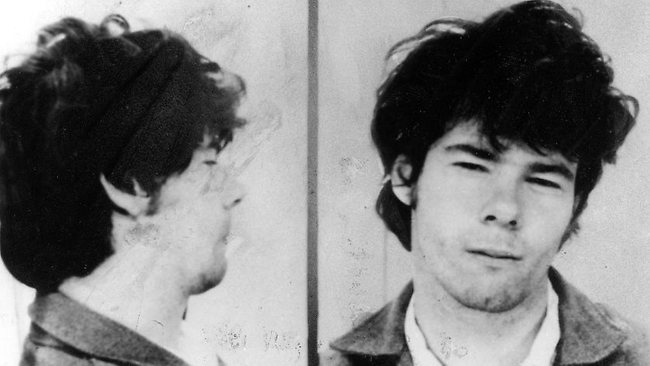

The inquest into the May 2004 murders of Christine and Terry Hodson is being held in Melbourne this week. The man who ordered their killing Carl Anthony Williams is once again in the public spotlight, perhaps for the last time. It took me a long time, nearly ten years, to fully understand what motivated him. Here was a family that was at odds with the law and the State, but also with the criminal elites that ran the underworld. They seemed to have materialised from the suburban ether, poor white trash from nowhere. But they had risen above the rest of them. There was a streak of rat cunning and resentment in the Williams clan that made them push back against much greater forces.

They had built a small empire in the space of a single generation and Carl was fully prepared to slaughter anyone who crossed the family. Their bloody feud with the Moran clan and the rest of the Melbourne big shots was the climax of an untold history. It was about ingrained poverty and disappointment, of generations beaten down, neglected and despised. The descent into crime and murder spoke of what happens to the self-esteem of people when they are denied the opportunity that others regard as a birthright. It’s the bitter realisation that the Australian ethos of the fair go is in fact a cruel joke. It’s the story of what happens when the have-nots finally get a grip on the main chance.

The Williams’ journey to infamy began in the squalor of a transit camp for the homeless and destitute on the northern fringe of Melbourne’s Royal Park in the mid-1940s. In the years after World War II, Camp Pell was a human tip for what many regarded as the detritus of Melbourne society. It’s almost forgotten now. It’s a memory that jars with the post-war prosperity story that most Australians learn in schools these days. This place of degradation and suffering has been transformed into an “Urban Camp”, a quiet patch of cultured bushland nestling between busy Flemington Road and the State Hockey Centre. Teenagers come here now for school excursions. Nice people from the affluent adjoining suburbs walk their dogs among the eucalypts and wattles, enjoying the serenity of this oasis in the urban jungle. It seems benign and peaceful.

In the 1940s, when Carl’s grandparents on both sides of the family came here it was far from that. Camp Pell was their last resort. It was a choice between this stinking sinkhole or the streets for the Williams and the Denman clans. To George Williams, it seemed that everyone he knew had come from Camp Pell. It was his first memory. And his bride Barbara Denman had been born there too.

The sprawling shanty town had begun as a camp for Taskforce 6814, the forces that US Supreme Commander General Douglas MacArthur had thrown together after the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbour in Hawaii in December 1941. As a military camp, it had been suitably hard and uncomfortable but it was only ever meant to be temporary. The soldiers had stayed in tents or Nissan huts, igloo-shaped iron sweat boxes with dirt floors and no insulation.

The place had acquired a sinister reputation almost from the beginning. In the space of two weeks in May 1942, an American serviceman Private Eddie Leonski stationed there had murdered three local women, gaining the sobriquet the Brownout Strangler. On Macarthur’s orders, Leonski was hanged at Pentridge in November 1942 but the scandal cast a morbid shadow over Camp Pell. Later, a rumour swept Melbourne that American military police had shot and killed a number of GIs and some locals who had been involved in a vicious mass brawl outside the Flinders Street Railway Station in December. The story went that the incident was covered up on MacArthur’s orders and the corpses were secretly cremated at Camp Pell and the ashes spread on the grounds. The story was apocryphal but it helped cement public notions that there was something evil about Camp Pell.

After the war, the camp was turned into a transit camp for homeless families who moved straight into the Nissan huts the Americans had vacated. It was supposed to be a temporary arrangement for one year while the Victorian Government built new state housing for the poor. However, it stayed open for ten years amid government inaction and growing public revulsion.

In 1947, the Building Trades Federation wrote to government saying that living conditions at Camp Pell were “worse than the worst slums in Melbourne.” At any one time, more than three thousand people lived in Camp Pell sharing communal washing and cooking facilities. When it rained, the camp quickly became a quagmire, a dismal playground for hordes of filthy children with no shoes and ragged clothes. In summer the iron huts were intolerably hot so many took to sleeping out in the open. There were frequent outbreaks of diseases like diphtheria and whooping cough, diseases of poverty and overcrowding.

Camp Pell kids were ostracised at local schools for being unclean and spreading illness and head lice. Carl’s uncles and aunts even found the teachers gave them a hard time for their ragged dirty appearance.

Despite occasional half-hearted attempts to tidy it up, Camp Pell remained “a breeding ground of physical and spiritual disease…an evil intolerable plague spot,” according to an editorial in the Argus newspaper in April 1953.

“Nobody with eyes to see could bring himself to call any such monstrosity as this “a housing settlement.” Camp Pell is, in plain language, nothing but a dump for human beings.”

Little wonder then that the settlement became known as “Camp Hell.”

Privately, the State’s leaders could only agree the conditions were disgraceful but there was simply nowhere else to house these poor families. A slum reclamation programme had begun after the war and many families had been displaced from cheap rental accommodation across the inner-city. A wave of middle class migrants from Europe had bought up many of the old tenements in inner- city suburbs like Richmond, Fitzroy, St Kilda and Carlton. The original inhabitants, many of whom had been living there for generations on cheap rent were given their marching orders.

There had always been a shortage of housing for the poor in Melbourne but by the late-1940s the situation was dire with evictions running at 100 a month. There was little sympathy for the poor souls forced to live at Camp Pell and a number of other transit camps around the state. It seemed to them that the migrants got a better deal than the poor families of the city, many of whom had sent sons and daughters to fight and die for King and country in the war. While the migrants were praised for their work ethic and family values, the Anglo-Celtic poor were reviled for their moral degeneracy.

In 1949, the state housing minister had complained his “big problem was the provision of accommodation for habitual drunkards, sex perverts and sub-normal people living in emergency camps.”

Barbara’s parents, Bill and Mary Denman were none of those things, just decent hard working folk who left their home in Fish Creek in south Gippsland to look for a life in Melbourne. Bill Denman was a qualified welder but work was scarce and accommodation virtually non-existent so the only alternative was Camp Pell. With a growing brood of children, they tried to make the best of what they hoped would be a short stay. They stayed for nearly five years until they had seven children crammed into their iron hut.

George’s family had lived a few rows away from the Denmans with his mother, two sisters and a brother. George’s father had been a wharfie though he spent little time with the family. In fact George was not sure that the man was even his father. “You only know your mother for sure don’t you,” he liked to say later. Despite this George had fond memories of Camp Pell. It was a hard life but they were together, sharing the hut with its dirt floor, huddling around the saw dust burner for warmth in winter and sweltering under the tin roof in summer.

Camp Pell was overrun with children, many of whom remember those days with nostalgia. George had cousins living nearby and they formed a gang of urchins who were always getting into trouble, cutting down trees for fun and generally running amok in the camp. They had their own catch cry: “Camp Pell kids. Camp Pell kids. Camp Pell kids are we. We’re always up to mischief, wherever we may be.”

Yet the camp was an extremely dangerous place for adults, especially under the seething smoky cover of night. The newspaper archives are full of stories of murders, robberies, rapes and domestic violence that were commonplace at Camp Pell. Police regarded the camp as the epicentre of crime in Melbourne.

But the kids generally were exempt from these horrors and, as kids do, adapted to life in the mud and filth. George Williams remembered nights roaming the grounds with other kids, seeing groups of men drinking around late night fires and hearing their stories.

In January 1950, as the rest of Melbourne warmed to the beginnings of post-war prosperity The Argus ran a story depicting barefoot children playing in the rubble of Camp Pell. “Is this our heritage,” the correspondent asked. “Broken huts and disused stoves are Camp Pell children’s playground.”

By 1953, there were 1300 children under 16, like George Williams and Barbara Denman living at Camp Pell. There were fears that “this evil pernicious place” might poison its inhabitants and the city in general.

In 1953 The Argus mounted a strident campaign to have the camp demolished.

“First the camp holds many hundreds of decent, hardworking men and their families, who want homes but can’t get them.

Second it holds an unhealthy number of work-shy parasites who wouldn’t move out of Camp Pell at any price.”

The social consequences of the moral contagion that had flourished in Camp Pell would be felt later, the newspaper warned.

“We can’t expect people, basically decent people, to go on living there for four, five, six years, as some of them have done, without contracting the moral diseases that Camp Pell breeds. We cannot expect children, basically decent children, to grow up in the miasma of this foul place as children are without becoming Dead-End kids – and graduating as Dead-End men and women.”

Families in the adjoining areas would warn their kids to stay out of Camp Pell as if the contagion of poverty could somehow be transmitted by contact with “the inmates” as the residents were described as if they lived in a jail or an asylum for the insane.

The public condemnation of Camp Pell brought the residents closer together. In 1954 they formed an association to correct the public perception that everyone living in their “suburb” was “an undesirable.”

“Every suburb has its undesirables – even Toorak” one resident, AF Gelsi told The Argus.

“But 99 per cent of residents at Cam Pell are good clean families who care for their homes and their families and behave as well as anyone,” he said.

Some families seemed content to stay in the camp indefinitely.

“I have lived here for two years and spent more than £400 on furniture,” said a widow, Mrs EM Stanley who was raising a 13-year old daughter.

“There are hundreds of other families here who have done the same,” she said.

In July 1955, the Labor Government of John Cain issued mass eviction notices to the residents without any plan of how to re-house them. With the Olympic Games coming to Melbourne the following year, the State Government had built 800 houses for the competitors in the Games Village but apparently could not find any funds to accommodate the residents of Camp Pell. Instead the residents had been told to move their belongings out as soon as possible so the decrepit hovels could be razed. The indignity of their treatment welded the people into mass action. Protest meetings were held to complain of the inhumane treatment.

“No self-respecting person wants to live in this filth and squalor but most of us have to,” the chairman of the Emergency Housing Tenant committee told a meeting of residents.

“As he addressed the open air meeting children played in pools of mud and slush,” the Argus reported.

“This is what we have to put up with,” said Mr AA Black, a member of the committee said his eyes sweeping the scene.

“We don’t want to live here. None of us with any decency would. But we have to have shelter for children.”

When the authorities came to forcibly evict residents, members of the Communist Party and trade unions helped families stand their ground, wresting back furniture and personal belongings and returning them into the huts.

Eventually sense prevailed and the camp was given a reprieve while government worked out what to do with the 600 families who stubbornly refused to move until offered proper housing. Despite all the outrage there was still nowhere to put these destitute people who seemed to threaten the moral health of the city.

In 1955 Liberal Party leader Henry Bolte came to power and vowed to put an end to Camp Pell as one of his top election promises. The last family left Camp Pell on May 31 1956, giving the Public Works Department enough time to clear away the remaining 50 huts before the Olympic Games came to Melbourne in November. It was not from a sense of pity or compassion. Bolte privately said that he could not allow Queen Elizabeth and husband Prince Phillip to gaze upon the filthy eyesore as they came in from the airport to open the Olympic Games.

The Denmans had already left Camp Pell in 1954 when Barbara was six but George’s family had been among the last to vacate.

Most families had been shifted to Housing Commission dwellings while others had found their own housing. George’s family had ended up in a rundown worker’s cottage in North Richmond that was only marginally better than the hovel they had left in Camp Pell.

But families who had lived at Camp Pell could never remove the stain, at least in the eyes of the good middle class folk of Melbourne. While they abhorred the conditions and castigated the government for its inaction there was a sense that the people living in Camp Pell were beyond redemption. Soon the chickens would come home to roost in the form of crime and social dysfunction. The vermin would infect the city.

“We hear of marriages breaking, men turning to crime, children becoming tough young dead-end delinquents under the ugly spell of Camp Pell,” one editorialist thundered.

“Is it surprising? The family that spend months or years in Camp Pell and comes out untarnished must be of uncommonly strong moral fibre.”

“Men, women and children are not only physically ravaged by life in Camp Pell; they are also irreparably damaged in spirit.”

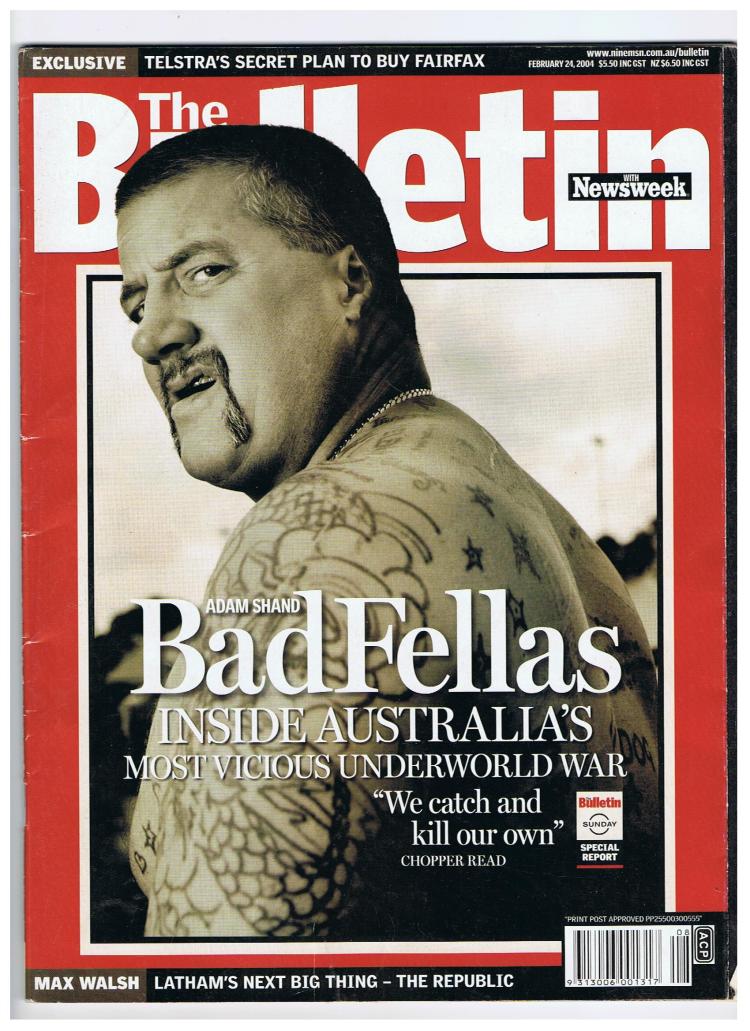

More than fifty years later, the moral arbiters were still passing judgement on the families who had passed through Camp Pell. Even though society had been tainted by drugs, violence and official corruption at the highest levels, the blame could still be sheeted home to individuals as if all was perfectly well on the high moral ground. At Carl’s death in 2010 radio broadcaster Derryn Hinch declared him nothing more than “a piece of greedy human flotsam.”

“Carl Williams is dead and believe me the world is better for his passing. It’s one more vote for a cleaner Australia. He was scum and don’t let TV shows like Underbelly ever fool you otherwise,” he said.

How laughable it was that Hinch and others could wish away half a century of social exclusion with the death of one man. There were thousands of people who recognised their own lives in Carl’s story. To them, it was hardly surprising that Carl had put family before the law or society’s norms.